Sujatha Mathai on Nissim Ezekiel 1. When did you first meet my father, Nissim Ezekiel? Do you remember anything specific or special associated with that first encounter? Further encounters? 2. What were your impressions of my father? How did these change, as you got to know him better? 3. Can you describe him in his professional work, such as writing, mentoring younger poets, art critic, working at the PEN? 4. Do you have an anecdote that you would consider sharing? 5. What is your favorite poem of my father’s? 6. Do you have any memories of me with my father, on any occasion? 7. Is there anything else you would like to add? I first met Nissim E. sometime in the 70s, though I’m not absolutely sure. I had been living in small- town Mangalore, after I came back from England. I found myself lonely, unhappy and adrift. I didn’t even know that people were writing poetry in English! After another stint in England (Liverpool), my (former). husband, got a suitable teaching plus surgery post in Bangalore. At last, I could join a Theatre Group again! I hardly thought about writing. Though my very first poem had been accepted by P. Lal. But I do remember Nissim’s dry sense of humour, which I liked. He was always very kind to me. Later I started writing more and decided to visit Bombay, where I have many aunts and cousins. I would always make an appointment to meet Nissim. What I noticed about him was his commitment to his work. He worked regularly at the PEN Office, always there, and available to writers and editors who wished to meet him. The dry humour was endearing, as were the postcards, with a few lines on them, signed Nissim E. One day I remember his inviting me for coffee at the Jahangir Art Centre( not sure if that was it), (or was it Samovar?) and we had a lovely chat about literature and people and books. Some people did say rather nasty things about him , but I went by my own experience. Later, he visited Bangalore, and I invited him to tea at my Cunningham Rd house. I was in the the throes of an unpleasant break-up, but tried to stay composed. We went once to see him or drop him to the Guest House he was staying at. I remember my little son saying to Nissim” Can this car fly like a chariot , through the crowd?” Nissim said he thought it could! When we moved to Bangalore I started sending a few poems to the PEN Magazine, edited by Nissim Ezekiel. He was very generous in accepting them, and making me feel I was , maybe? - a poet? After all the misery and isolation I had felt in Mangalore, my life was enriched. About this time, my father, a Professor of English, wrote that he had been invited to a Poetry Seminar in Jaipur. Would I like to come? We would stay with his very dear, old friend P.S. Sundaram. I agreed. It was there, I first met Nissim Ezekiel! He seemed very friendly and easy to talk to, not highbrow or pretentious as some of the poets seemed to me. He remembered the poems I’d been sending him, and asked me to read a couple of them, including In the Market Place, which first appeared in the PEN Magazine. Later, I was invited to join in a discussion with Nissim on AIR. I don’t remember what it was about. Nissim was very generous to me. He gave sound criticism, but always used my poems where he could. I’LL never forget the thrill and shock I got to find a short poem of mine w a black and white drawing. (I thInk the poem was called The Journey) on the front page of The Tiimes of India, Ed by Nissim! Once he gave me a lovely bit of editorial wisdom. I had a line about “held together by sacred bonds” He suggested I change the word sacred to secret. I immediately accepted it as “just right.“ It was the most innately apt editorial advice I ever had. He solidly supported my book The Attic of Night. I still have the PC on which he wrote: “ I believe that your book will go into the third and fourth and more editions.” The Attic of Night sold a 1000 copies in its first print, (it went into a Second Imp. and actually brought me some royalty! Nissim was on the Board of our Poetry Society of India.The last time I met him was at the Governing Body meeting of the Poetry Society. He seemed ill and disconnected and could not respond to my questions. It was the beginning of his illness, and I hoped he would get the care he needed. I never saw him again. I am so glad to have his Collected Poems. I think The Night of the Scorpion has become his best known poem. I love many other of his poems, especially “Background, Casually,” & am happy to have his Collected Poems.

Shalva Weil on Nissim Ezekiel (Thank you Shalva for your words about my father. They are much appreciated.) I first met Nissim Ezekiel in Bombay. I already had a doctorate in anthropology after conducting 3 years’ fieldwork among the Bene Israel in Lod, Israel. Sara Ezekiel, a senior member of the Bene Israel community, had adopted me as a grandmother and referred me to Nissim since they were friendly from the Jewish Religious Union. Nissim was very much into that non-orthodox, Reform/Liberal type of Judaism with prayers in English. So it was early in the 1980s that I met your father and also visited your home and met your mother. She was more traditional, I felt. I often wondered how she managed to live with some of his poems. My impressions of your father never changed. He was always warm, intelligent, fun, witty and irreverent. Of course, Nissim wasn’t only a poet. I followed his development avidly. He was a playwright, a reviewer and more. Since my major interest was Nissim as a Bene Israel, my favorite poem was and is “Jewish Marriage in Bombay” with references to Jewish law and custom, as well as real insights into ceremonies and what we call ‘love’. However, today I realize one has to view Nissim in wider perspective against the backdrop of the evolving Bombay cultural scene. I met some of his friends from the Bombay Progressive Artists group. They were all ex-Bohemians, rebels and multi-faceted. So while Nissim could feel comfortable in the synagogue, and at the same time uncomfortable, so too he sat on the margins of some of the greatest artistic episodes and artists that India has produced. Today, if you visit me in Jerusalem, you are greeted by a wall mural painted by F. N. Souza’s grandson, Solomon, a young graffiti artist who paints like him and lives in Jerusalem as a Jew. I tell Solomon about Nissim and we have found photos of them together. Nissim’s visit to Jerusalem in June 1995 was a personal tribute to me. Everyone said he wouldn’t accept my invitation, but I knew he would. At the time, I was Chairperson of the India-Israel Cultural Association (with Zubin Mehta as President) founded in 1992 after diplomatic relations were established between the two countries. It was the official friendship association between India and Israel, but I and my committee preferred to focus upon culture rather than commerce and defense, as today. I asked the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs to invite Nissim and pay for his air ticket and accommodation at Mishkenot Shamanism in Jerusalem, where international literary stars are hosted. He stayed in those beautiful surroundings opposite the walls of the Old City, and it was there that we held a well-attended poetry reading. After I opened the meeting, the Israeli poet Amir Oz introduced him. Some of my committee members knew Shimon Peres, who was a great admirer of Nissim Ezekiel. We organized a reception with Peres, which thrilled Nissim, and also Shimon Peres, and Nissim read out one or two of his poems. Then Nissim moved to my residence in Jerusalem. We held another poetry reading for the members of the Bene Israel community in Lod, where I had lived doing my fieldwork among the community in the 1970s. It was during Nissim’s visit to Jerusalem that we realised fully that he was suffering from early Alzheimer This must have been Nissim’s last foray abroad. He was anyway itching to return to Bombay, the city of his love and his dreams. -Shalva Weil

- When did you first meet my father, Nissim Ezekiel? Do you remember anything specific or special associated with that first encounter? Further encounters?

My first meeting with Nissim Ezekiel was at his offices [at the University of Bombay]. This was in June of 1973. It was pouring. I wore my hair long in those days, dressed in a kurta and jeans – a sign that I felt European [my father is Brasilian and my mum a mix of Indian and Persian], but was trying to “belong” somewhere – India, at that time. I couldn’t understand why I needed to “belong” to India, but writing in English in India felt dissonant. Anyway…

Nissim was dressed in a yellow shirt with a tiny floral pattern; a bush-shirt that he wore outside his pants [I came to realise this was characteristic of him]. He was serious, but looked kind. He shook my hand and asked me to sit. There was another person in the room with him. It was Vrinda Naber. I didn’t know who she was, but was immediately on guard. I didn’t think she had any right to be there in that loud pink blouse she was wearing. She stared at me sphinx-like and refused to get up and go.

I was already intimidated at being in the presence of a poet who was at the pinnacle of his career and felt that somehow things were going to go down like a lead balloon. Anyway, I plucked up the courage to speak to your dad.

So pulling out a sheaf of paper from my “bagal-thaila” [I think that’s what you called those cloth shoulder bags we all carried in those days]. Looking hard at Ms Naber, I put the poems in front of Nissim. He read the first one without any change in his expression; then the second and the third. They were all short poems. Then he said: “Well, Raul, that’s good. But what do you want to achieve as a writer?”

“I want to be like John Keats,” I replied. I had the romantic notion that I would write poems like Ode to a Grecian Urn and Endymion, contract T.B. by the time I was 27 and die of it. I didn’t make that confession to Nissim, but I think he got the feeling that I was a poet-in-a-hurry. He looked me straight in the eye and said: “These works are a good beginning,” he said, “But if you want to be like Keats, you’ll have to put in a lot more work. Keats wrote hundreds of poems before he wrote the “right” ones… before he could be recognised…” he said.

I am not sure what I wanted to hear from Nissim about my work. I was irritated that I had to hear this in Ms Naber’s presence. He asked me where I was studying, who my teachers were. I named Eunice De Souza and Adil. “You’re in good hands,” he said, enigmatically. I felt a mixture of embarrassment and anger [irrational anger directed mostly at Ms Naber].

The next day I reported this to Adil, who had set the whole thing up. Adil calmed me down. He said, “Well… Nissim is right…If you want to emulate Keats, you’ll have to work really hard at your work,” he opined. “But that woman, Vrinda…” I said, and then I stopped myself and thought about Nissim’s advice at “working” on my poems instead.

There were several encounters at Samovar, and at a South Indian restaurant on a Marine Lines. We became much friendlier as our encounters multiplied. I kept filling him in with what I was up to and two years later when Santan Rodrigues, Melanie Silgardo and I founded Newground published our book 3 Poets, I gave him a copy. This time he had a BIG smile on his face. He promised to read the poems, put his hand around me and said, “Keats…” Then he smiled a big smile and left.

- What were your impressions of my father? How did these change, as you got to know him better?

I felt that Nissim was a kind man. I could see that in his face. But I also knew that he was a demanding artist. After all he didn’t get there by dashing off the first things that came to his mind. At a subsequent meeting he told me, “The gift of writing makes you an artist, but you have to develop the attitude of a craftsman. And you can only do that if you work at the gift… chip away at the extra bits, trim the rough edges… chisel away at the words… fine-tune the idiom…craftsmanship is just as important to the artist as being aware of the art itself.”

I felt close to him after meeting – and eating at the table with him. I stopped feeling alone even though there were times when nothing much was said… somehow I felt that everything that mattered was understood.

- Can you describe him in his professional work, such as writing, mentoring younger poets, art critic, working at the PEN?

Nissim and Adil were the only mentors I had…have… When I have a problem expressing a metaphor, my urge is to go back to their work, or a conversation we may have had, to find a way to smooth the rough edges of my own work. Adil fed my artistic fire… Nissim not only fed that fire, but he taught me how to stoke the fire. I later realised that he worked on board a ship. Our bond grew exponentially after that because my own father sailed supply ships during World War II…After that we found many more things to talk about. But every time we met, no matter what we talked about, he always had a tip about writing to share with me…he told me to watch out for glibness and trite imagery… “You have a gift for writing,” he used to say, “Writing comes easily to you, but beware of the things that come to you easily,” he said.

I attended all of his P.E.N. lectures and other programmes. I devoured his art criticism and in many ways, I grew to appreciate Sabavala, Anjolie Ela Menon and others purely on the basis of his art criticism.

But by far, my favourite work of criticism of your dad’s was the essay Naipaul’s India and Mine. It is a work on par with anything George Steiner or Susan Sontag or Auden have written… the greatest rebuttal to Naipaul by anyone anywhere in the world… including Paul Theroux.

I don’t think that I am alone in glorifying Nissim for all the things you have asked me in this question. Santan and I used to speak a lot about how much he meant you the ports of our generation… Later he consented to be guest editor of Kavi. It was an enormous honour for us, but that was Nissim… generous to a fault, someone who gave of himself completely…

- Do you have an anecdote that you would consider sharing?

I was part of the group that was at that restaurant when Nissim found that bug in his food… you know the rest. It was typical of his gentleness… and about being generous to a fault.

- What is your favorite poem of my father’s?

You’re putting me on the spot here… It’s hard to single out a “favourite poem”…I have several, but for brevity’s sake I’ll say “Night of the Scorpion” “Background Casually”, and if I may, everything in Latter Day Psalms

- Do you have any memories of me with my father, on any occasion?

Just one… I saw you with him once at the Jehangir Art Gallery. He introduced you to me. I couldn’t get over how alike you looked. You still smile the same way and every time I look at photographs of you I remember him. I thought how fortunate you were to have him as a father. Later, I learned you have a brother too – Elkana – who I believe had something to do with drama.

- Is there anything else you would like to add?

I still read Nissim’s work, not simply to enjoy his poetry, but often to learn how to resolve a thought in danger of overtaking the heart of an emotion. “Night of the Scorpion” is a classic example as is everything in Latter Day Psalms. He is also a master of how to prune a line… to distil it to the essence of an emotion… how to strengthen and chisel [his word] an image; to make it “everything” to the poem…

Usha Kishore in conversation with Kavita Ezekiel

Remembering Nissim Ezekiel, the Jewish Indian poet

Nissim Ezekiel, an Indian Jewish poet, playwright, editor, and art critic was one of the foundational figures of post-independence Indian Poetry in English. Ezekiel is considered the Father of Modern English Poetry. Ezekiel was honoured by the Sahitya Akademi award in 1983 and the Padma Shri in 1988. These are just two of his many accolades. He was Vice-Principal of Mithibai College, Mumbai and Professor at the University of Bombay, until his retirement. He also edited The Indian P.E.N.

Usha Kishore talks to Ezekiel’s daughter, Kavita about the Jewish elements in his Poetry.

Usha Kishore (UK): Shalom Kavita, I am delighted to be able to speak to you about your esteemed father, the late Nissim Ezekiel and his work.

Kavita Ezekiel (KE): Thank you Usha. It is a pleasure to speak with you about my late father’s work.

UK: Let me begin with Indian Jews. The Indian Jewish identity cannot be considered in a western context. The American Jewish author Nathan Katz[1] feels that Jewish history is at its happiest in India as there has been no religious persecution, unlike Europe and elsewhere in the world. What do you feel?

KE: Growing up, I never experienced any kind of religious persecution. I was never conscious of being Jewish as something separate from the rest of India. We mingled freely with everyone – Muslims, Christians, Parsees, Anglo Indians and Hindus. I always felt that people were very interested in my Jewish heritage. About the only time, I remember being judged for being Jewish was in school when we were studying The Merchant of Venice, when classmates teased me and called me ‘Shylock.’ Also, at boarding school, when I was nine years old, I was accused of ‘killing Christ’ and I wrote a poem called ‘The Crucifixion’. I take this to be the consequence of stereotypes engendered through literature. And, studying the Bible at a Christian school, exerted a strong influence on children to stigmatize the only Jewish student in the classroom. Looking back, I now realize that it was childish ignorance, but at the time, it was hurtful and insensitive. Ironically, I had a similar experience to the one my father describes in the poem, ‘Background, Casually,’ except I attended a school run by Protestant Christian missionaries.

I went to Roman Catholic School

A mugging Jew among the wolves.

They told me I had killed Christ.

(‘Background, Casually)

The distinctive experience of Jews was that they were held in high esteem and never faced discrimination in India. In the later part of the 18th Century, many Bene Israelis moved to Bombay (Mumbai), Ahmedabad, Karachi and Calcutta and distinguished themselves in many fields such as Education, Law and the Armed Forces, including the British Army’s ‘Native Forces’, and its successor, the Indian Army. Ezekiel highlights his ancestry in the most defining poem of his life, ‘Background, Casually’:

One among them fought and taught

A Major bearing British arms.

He told my father sad stories

Of the Boer War…

UK: Nathan Katz opines that the Indian Jewish identity is created by the community’s interaction with the Hindus and other Indian religions. Do you agree with this?

KE: I don’t know if the Indian Jewish identity is created exclusively by the community’s interaction with the Hindus and other Indian religions. They had a pretty strong sense of their own identity. Certainly, the close relationship with the Hindus might have influenced their identity and was largely because the Bene Israeli Jews blended seamlessly into the cultural milieu, while retaining their own customs and traditions. They spoke Marathi alongside English, ate Indian foods, the women wore sarees, and did not experience any anti-Semitism. Prayers were recited in Hebrew, and regular visits to the synagogue on festival days was part of their cultural identity. They were accepted by the Hindus with all these traditions. The Bene Israeli Jews inter-married with Catholics, Parsees and Muslims as well. Whenever I had asked my father whether we were ‘Jewish Indian’ or ‘Indian Jewish’, he had always replied ‘Both’!

UK: I feel that Ezekiel does not explore the cultural mechanisms that define India’s diverse Jewish identities, but he responds to the changing cultural and political atmosphere of Independent India. Do you agree?

KE: While Nissim Ezekiel was conscious and aware of the diverse Jewish identities in India, the dominant themes in his poetry and writings were mainly concerned with India and ‘Indianness.’ I don’t think that the political changes or atmosphere of ‘independent India’ necessarily took centre stage in his poetry. He was immersed in the experience of being human, of change, of his own inner struggles, but wrote as an observer, detached from the experience.

UK: Do you think that Ezekiel’s poetry addresses the minority status of the Indian Jews and their exodus from India and also provides a dialogic response to Hinduism?

KE: Nissim Ezekiel was aware of the exodus of Indian Jews, but he does not write about it. I remember him clearly saying about the desire of Indians to emigrate ‘west’ to ‘make it.’ I quote him: ‘Who will remain to do something for India?’ There is no ‘dialogic response’ to any faith. The writing of poetry was central to his life. He always taught me that the important truths of life are expressed in all religions, be it Hinduism, Islam, Judaism or Christianity. My father was also widely read in the sacred texts of all religions and interested in different ways of approaching the search for truth. He chose to remain in India, a country he loved deeply, as do I, and our family did not emigrate to Israel.

I have made my commitments now.

This is one: to stay where I am,

As others choose to give themselves

In some remote and backward place.

My backward place is where I am.

(‘Background, Casually’)

UK: How does Ezekiel’s poetry reflect on his Jewish identity? Do the issues of identity and alienation figure in his work?

KE: There is no overt ‘Jewish identity’ which emerges as a theme anywhere in Nissim Ezekiel’s poetry. No doubt, being born Jewish influenced his use of language and the feeling that the man is actuallypraying to his God in many of his poems. Irrespective of religion, anyone could relate to those ‘prayers’. It does not mean that the sentiments expressed e.g. in Latter Day Psalms, are in any sense ‘Jewish’. At the end of ‘The Latter Day Psalms,’ he does say “Now I am through with the Psalms/they are part of my flesh.”Much later in life, towards the end, Ezekiel began to read the Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism). But I recall that his interests in religious texts were eclectic, not driven by religious sentiment, but the keen inquiry of an avid learner, devoid of any pre-judgement. In his poem ‘Jewish Wedding in Bombay’, he mentions that his father:

… himself had drifted into the liberal

creed but without much conviction, taking us all with him.

My mother was very proud of being ‘progressive.’

UK: Can the poem, ‘Background Casually’ be considered the poetic autobiography of Ezekiel, highlighting the issues of identity and alienation, nationality and marginality?

KE: The poem is clearly autobiographical and the themes you mention do occur naturally, since they were an integral part of the poet’s experiences. Ezekiel outlines his struggle for personal identity, as he tries to socialize with students from diverse faiths in school.He is also bullied by the boys from different faiths as he describes it ‘a mugging Jew among the wolves.’ The search for identity continues:

At home on Friday night the prayers

Were said. My morals had declined.

I heard of Yoga and of Zen.

Could I, perhaps be rabbi-saint?

The more I searched, the less I found.

However, Ezekiel has always identified himself with India and felt completely at home there. There was no conflict with a search for nationality. Many poems speak of his Indianness. I don’t think he ever felt marginalized. Ezekiel was a natural outsider, being born Jewish, but an insider, as he loved his country, and particularly the city he was born and raised in, which was Bombay. He highlights this in Poster Poems’:

I’ve never been a refugee

Except of the spirit,

A loved and troubled country

Which is my home and enemy.

UK: The poem ‘Background Casually’ refers to: My ancestors among the castes/ Were aliens crushing seed for bread/ (The hooded bullock made his rounds). Am I right in thinking that this is the reference to Ezekiel’s cultural connections and the Shanwarteli community?

KE: Yes, you are right; the quote is a reference to the Bene Israeli community, who were oil-pressers. The reference to ‘aliens’ signifies that they clearly were outsiders to the local community. The term ‘Bene-Israel’ refers to the largest of the three Jewish communities in India (the other two are Cochin and Bagdhadi Jews). According to legend, they descended from ‘Seven Couples’ who were the remnants of a shipwreck near the village of Navgaon, on the Konkan coast in India, near Mumbai. Because of the centrality of the Prophet Elijah in their oral traditions, their ancestors may have lived in the time of Elijah in Israel and their arrival in India dates anywhere between the 8th century BCE and 6th century CE. They became assimilated in the coastal communities, taking up farming, carpentry and mainly, oil pressing. Because they observed the Jewish Sabbath and did not work on Saturdays, they came to be known as ‘Shanwar Telis’ or ‘Saturday Oil Pressers’. Today, the Bene Israeli number about 5000 in India and 40,000 in Israel, after an exodus of Jews from India in the 1950 and 60s.

UK: How does your work as a poet reflect your Jewish identity?

KE: Several of my poems in the last few years are based on Jewish themes. As I grow older, I have also begun to explore my Jewish roots, and my poetry is an attempt to come to terms with my cultural heritage. The poems are influenced less by me being religiously Jewish, and more by the memories of growing up in a Jewish home, with all its rituals, traditions, beliefs, festivals. At the Christian school, I attended, I learned much from the Bible with a focus on the New Testament. A couple of my poems, like ‘Alibaug’ and ‘Miracles’ have Christian references. ‘Alibaug’ is a poem with a specifically Jewish theme, set in the then predominantly Jewish village of my childhood, where my uncle owned a grain mill. Alibaug has changed much now, with all the rich people buying homes there, and the hotels that have sprung up.

I think a good portion of the Jewish prayers being in Hebrew made it difficult for me and could havecontributed to my lack of knowledge of the essence of Judaism. In recent years, I have been deeply affected by the Holocaust – reading about the persecution of Jews, their suffering and the senseless slaughter of 6 million people.

Several of my poems over the last few years are based on Jewish themes as a reflection of my exploration of my Jewish roots and cultural heritage. The poem ‘Alibaug’, is one example.

I miss Alibaug

I don’t know when I can return

To the land of my ancestors

The land of the Shanwartelis, the Oil pressers

Having attended a Christian-missionary school in Bombay, the teachings of Jesus were a strong influence on my life. The poem ‘Alibaug’, makes reference to a story I loved.

I had heard of Jesus in school

Of how He walked on water

And His command to still the storm,

I remember praying to have that kind of faith

My poems ‘I Still sing The Shema’ and Light of the Sabbath,’ based on Jewish themes have been recently published in Indian Literature and Harbinger Asylum.

‘I Still sing The Shema’[2]:

I watch movies about the Holocaust I cannot bear to watch; I become an enraged bull

I leave the room and re-enter like the Matador determined to conquer the beast

I wish I had The Matador’s nerve and skill.

‘Light of the Sabbath’[3]:

Each Friday evening, we squeezed

The purple grapes of Faith

And each Saturday she read

All one hundred and fifty Psalms

UK: How has your father’s work influenced your poetry?

KE: My father’s work has influenced my poetry in a sort of unconscious way. I had the ‘lived life with him,’ so many of the ideas, values, and attitudes to life he passed on to me, find expression in my poems. Of course, the style and format of my poetry is different. I have my own voice, and am so glad to have discovered it, and am continuing to hone my craft. So many of the themes I write about, for example the theme of Nature, have been influenced by my father.Every poem I write makes either a direct or indirect reference to him. Of course, being raised by him, deep down in my subconscious mind, things surface, and get written into the poetry.Both of us use amore direct and colloquial style and write a great deal about ordinary things. Whatever shapes my life, shapes my poetry, and of course that has been the same for him, as for all poets. My father has played such an important role in my life that of course things he taught me, are a permanent part of my psyche. He was a true intellectual, though. I have never tried to imitate him, nor do I feel like I am walking in his shadow. Rather, I know that I am walking alongside him, sharing space with him in the world of poetry, if ever so slightly. It is amazing and humbling to have a poet of his stature as a father. He always spoke of his faith in my potential, and my hope is to fulfil that potential, and preserve his legacy, which is more important to me, in many ways, than my own writing.

Suppose I were a Shooting Star

I would want to be seen

That would be my only meaning

What is there after all

In shooting across the sky

And being burnt up…

(‘The Eternal Ego Speaks’, from Ezekiel’s Poster Poems)

My father loved the stars

There was a surge in the twinkle in his eyes

Like a gently rising ocean tide

When he spoke of the stars,

Shooting stars were his favorite…

(From ‘The Many Things My Father Loved’by Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca)

UK: Kavita, Thank you very much for this enlightening interview. Your father will always be remembered for his eclectic verse and his dynamic poetic sensibility. Best Wishes with your writing and future poetry collections.

KE: Thank you Usha. I have enjoyed this conversation with you.

An excerpt from Kavita’s memoir, about Jewishness, has recently been published in the October issue of SETU magazine.[4]

[1] Nathan Katz, Who are the Jews of India? (California: University of California Press, 2000).

[2] Published in Indian Literature (New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, July / August 2020)

[3] Harbinger Asylum (Fall Issue, 2020)

[4] https://www.setumag.com/2020/09/banana-lane-childhood-memoir.html

♣♣♣END♣♣♣

https://www.mid-day.com/mumbai-guide/things-to-do/article/her-fathers-daughter-23205382

Keeping Nissim Ezekiel’s legacy alive

Updated on: 17 December,2021 10:23 AM IST | Mumbai

Fiona Fernandez |

Kavita recalls that he chose happiness in all circumstances and was concerned for the needs of others; these among other values were passed on to her. Illustration/Uday Mohite

“Suppose I were a shooting star, I would want to be seen, that would be my only meaning, what is there, after all, in shooting across the sky and being burnt up? But being seen! That would be another thing” – Nissim Ezekiel (d: 2004)

On busy Dr E Moses Road is an oasis of calm. It is the Jewish Cemetery, the final resting place for Mumbai’s Bene Israelis. Among those who are buried here is Nissim Ezekiel, the famous bard. His words (above) etched on his epitaph echo the journey and contribution of the community.

Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca

Found in translation

“I read Professor Dalvi’s translation of poems into Marathi on his Facebook page. Many were of poets my father admired, like William Carlos Williams and Rilke. I enjoyed his translations, and began communicating with him. Marathi is my first language along with English. It is the language of the Bene Israel community of Indian Jews. My husband and I also speak Marathi at home, although his first language is Konkani. My father had co-translated the poems of the well-known Marathi poet Indira Sant. Last week, I requested Professor Dalvi to translate my poem,” shares Ezekiel’s Canada-based daughter. “Professor Dalvi is an accomplished and widely published poet. I have been co-translating my father’s poems into Spanish, and hope to translate them into French someday,” she reveals.

For Dalvi, Nissim was a familiar, avuncular figure while he was at architecture school, walking around the same places as he did in South Bombay. “I saw Nissim before I read his poems in books at the British Library. He was easily recognisable because of his long flowing hair and metal-framed glasses. I was struck by his strong poetic lines, his observations, his use of language and how he got the everyday speech exactly right.” Dalvi’s favourites are Goodbye Party for Miss Pushpa T.S. and The Patriot.

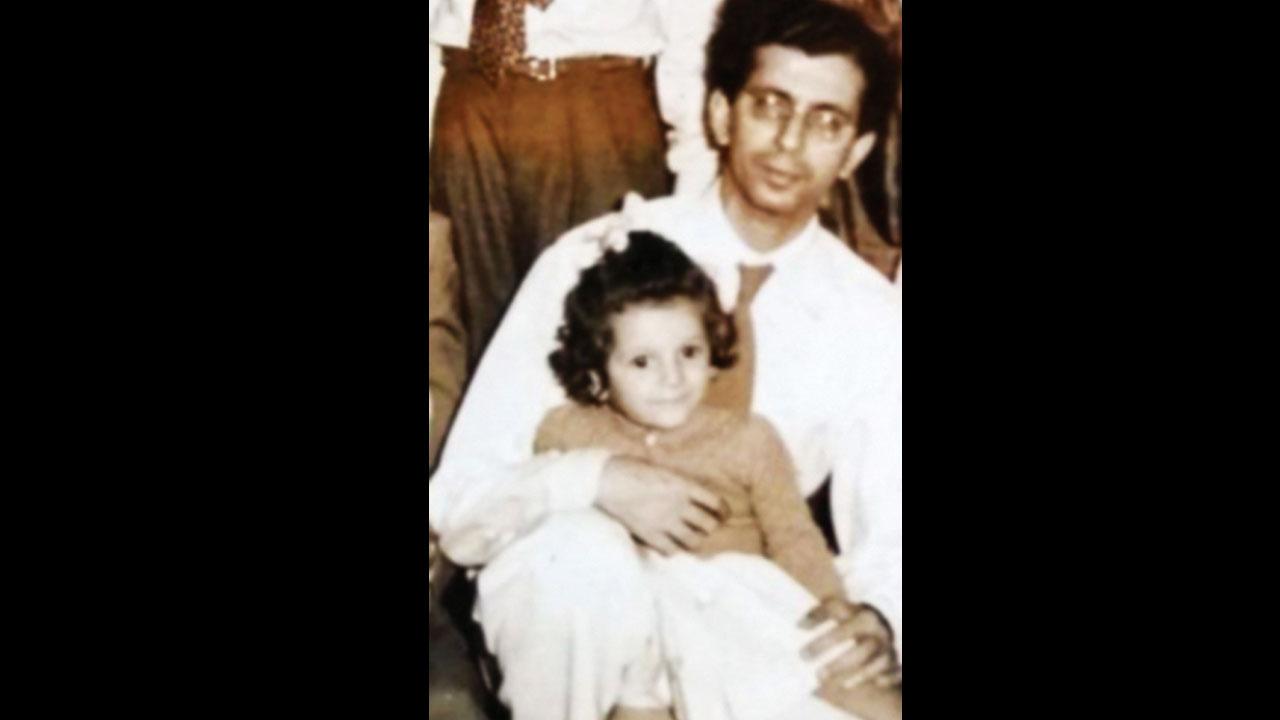

Kavita with Nissim Ezekiel at a wedding

Kavita with Nissim Ezekiel at a wedding

He was well aware of the risks that come with this translation since he began translating from English to Marathi recently. “Most of my work is the other way round, translating Marathi poems into English. I attempted translating English poets, both Indian and international, to see how their poems sounded in Marathi, for my own pleasure. I am grateful to Kavita for urging me to translate Nissim’s poetry, and her own ode to her father.” Dalvi attempted these with some trepidation but feels he got the spirit of the poems. “Of course, they have to stand as Marathi poems on their own. The act of translation must be subsumed in the final product, never to stand out.”

While working on these translations, two things struck Dalvi. “The atmospherics in the poem — night, rain, diabolic tail, very noir and the prayers that I tried to refashion with rhythmic incantations. It is poetry that sweeps in several directions, and I was aware of that while I tried to put the translation together.”

Daddy’s poetry

Kavita has fond memories of watching her father at work, “I watched with great interest and some amount of amusement, the process and technique my father employed in the writing of his poetry. I have described this in my poem, How Daddy wrote His Poetry. He usually took one puff of a Menthol Cool cigarette and left it to die out in the ashtray, placed a handkerchief over his eyes and lay down on the bed, then back to his desk after a few minutes as the lines came to him, writing them down on lined paper, then back to the bed again. It was a kind of a set rhythm,” she reminisces. In comparison, Kavita writes at her desk, in the office space that she shares with her husband. “When I set out to write a poem, I am not conscious of my father’s influence, but once I’m done writing and revising, I realise his strong influence. I have developed my own voice, but we share a few similar themes, such as a love of nature and ordinary things, as well as a more conversational and direct style of writing. Sometimes, even the tone of our poems is similar.” She admits, however, that the depth and breadth in his writing will need many lifetimes to achieve.

Mustansir Dalvi

There is something about poetry that attracts children, both to read, and write it. And Kavita wrote poetry from an early age, though she did not think it had much to do with her father at that stage, except unconsciously. “He was quite excited though, that I had become interested in poetry. I had a long career in teaching in Indian schools and colleges, and in private schools overseas, and was deeply committed to the profession. I published my debut collection in 1989. Subsequently, there was a long hiatus, working full time, raising two children, and moving to another country. It was only after I retired that I resumed writing poetry. I enjoy writing, but it is hard work and my thoughts go back to my father with every poem I write. He juggled a full-time teaching career with his writing, mentoring other poets, and immersing himself in other interests like art and theatre.”

Unlike the weight that offspring of successful people tend to carry, it was easy for Kavita. “My father never put any pressure on me to write. In fact, he said he felt people would think he was promoting his daughter. He was very conscious of that fact. I believe, from the messages I receive from individuals whom he mentored, that he was very proud of me. He even carried my first book of poetry [Family Sunday and Other Poems, 1989], with him to Israel, when he was invited there in 1995. I respected his wishes to not be involved in my writing, though it was a difficult decision, especially for my mother. He devoted all his time and energy to mentoring other younger poets. I am certain my writing career would have taken a much different turn if he had done the same for me.”

Legacy matters

Kavita is keen to keep his legacy alive. She discusses his poetry with today’s younger generations of poets, who might not be acquainted with it. “I also take every opportunity to introduce him to students of poetry overseas. My father was a foundational figure in the postcolonial literary history of India. Contemporary poetry cannot be studied in a vacuum.”

She is working on a personal memoir to commemorate the centennial anniversary of his birth. “It will be a challenge to record so many special memories of growing up with an interesting and ‘larger than life character’. Every anniversary is a reminder of his wonderful achievements and how much fun it was to be in his company. He was a great storyteller. He also had a sweet tooth, though he ate everything in moderation, so we will celebrate with cake on this occasion!” she signs off.

Nissim and Bombay

Ezekiel had a deep commitment to the city of his birth; it featured in many of his poems. Kavita quotes from Island, “I cannot leave the island/ I was born here and belong.” She also shares from Background Casually, “Others choose to give themselves/ In some remote and backward place/My backward place is where I am.” She had written poems to celebrate his love for the city and hers as well. “As he grew older and needed to be cared for, I invited him to live with us in Mussoorie, where I was teaching English in an international school. He wanted to join us but did not wish to leave Bombay. Although many Jews left for Israel, he stayed back. He believed that if everyone left, ‘who would do something for India?’ He had wanted to do something for India from an early age. He was at home here, and specifically, in Bombay,” she shares.

Kavita, the poet

Kavita recalls a poetry reading session where Ezekiel was asked about his favourite poet: “He replied, ‘My daughter, Kavita.’ That wasn’t meant to exclude my siblings [he wrote poems about them too]. He had named me symbolically, and perhaps, even prophetically! That might have had something to do with it. He had obviously put a lot of thought into my name.”

Jewish Legends

Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca

Image credit – Project Gutenberg

I married my husband in 1980. He was Catholic, a Mangalorean Christian. I had many friends of Goan origin in college and was not aware there were other sects of Christians as well, in Bombay. I had attended a school run by Protestant missionaries, where I gained in-depth knowledge about the New Testament. My husband wasn’t surprised that I was Jewish. With a last name like Ezekiel, it was almost a dead giveaway. He introduced me to his uncle who was a Bene Israeli Jew, the same community of Jews that I belonged to. In the early days of our marriage, we did not talk much about being Jewish, or much about Christianity. We lived the truths each of us had learned. We were united by love and our different backgrounds created no conflict. When we had children, I raised them by the tenets of the Ten Commandments and the universal laws of gracious living my parents and grandparents and my husband’s family had taught us.

My husband did mention though, that he had read the novel, Exodus, by Leon Uris, four times, starting in Grade 5! The reason for this massive endeavour was that his favorite aunt was marrying a Bene Israel Jew, and that triggered an interest in Judaism and the story of the founding of modern-day Israel. I had started to read Exodus but found it too long and gave up. I have often discovered, ironically, that sometimes people are more interested in the backgrounds of others from a different religion or culture, than their own. After marriage, we worked for a Bah’ai school in a hill station, an eight-hour bus ride from Bombay, and learned about yet another religion.

At home, we lit the Sabbath lamps on Friday and on Saturday night. The prayers were recited in Hebrew. At my grandmother’s home, an older aunt who lived with us, had a prayer book with side-by-side Hebrew and Marathi prayers. I could follow the Marathi well, as that was the language spoken at home, along with English. It was my aunt who taught me much about the observances of Judaism. My poem ‘Light of the Sabbath’ recounts the ritual.

Light of the Sabbath

Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca

Sacred Fridays of the Sabbath lamps,

An aunt’s faithful hands squeeze grapes

She allows me to squeeze just a few.

Purple juice-stained hands in purple glass,

Steady purple flame rising to Him who listens,

Meaning of *The Shema revealed.

Hebrew, English and Marathi prayers flood the room.

God is a linguist, understands all languages,

He doesn’t need a translator.

* The Shema – Jewish prayer: Hear O’ Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.

One day, I can’t remember exactly when, my husband asked if I knew the legend on the origin of the Bene Israel Jews in India. I didn’t even know there was a legend! No one in my family, as far as I can remember had talked of our origins. Growing up, we were one world in Bombay and people hardly cared what religion you belonged to. We mixed and mingled freely, and our customs and traditions were respected, as we respected those of our Muslim, Parsi, Christian neighbours, and our Hindu friends. And we took part enthusiastically in all their festivals. That was the magic of Bombay!! We observed the customs and traditions of Judaism but were not orthodox Jews. I remember being told a few stories with a moral at the end, but no Jewish legends. I still remember the words and tunes of many Marathi songs one of my aunts taught me. These were popular Marathi songs, unconnected to any legends.

My paternal grandparents, with whom I lived since the age of ten and as a baby (going there directly after my birth), never spoke of this legend. Interestingly enough, I still have in my possession the book my grandfather, Moses Ezekiel, had written about the Bene Israel Jews in 1948. He was Head of the Science department at Wilson College in Bombay, and also the Principal of a college in Nadiad in Gujarat, India. In his book, he mentions that he had travelled deep into the interior of the Kolaba district to collect plants (he was a botanist) and collected a great deal of information about the way of life about, what he calls ‘this microscopic community.’

In the first chapter of the book, he documents several differences of opinion regarding the exact date of the arrival of the Bene Israel Jews. One scholar, the late Dr. Wilson, says they belong to “The lost Ten Tribes of Israel’’. He had given a short account to the Bombay branch of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1938. He speaks also of Dr. Claudius Buchanan who was engaged in “Antiquarian Researches” arrived at the conclusion that ‘the Israelites who lived in Rajapuri and some other provinces in India, immigrated into the country before the commencement of the Christian Era’. He mentions a geographer who speaks of a port situated between Binda River or Bassein Creek and Mahad. ‘It is highly probable that the ancestors of the Bene-Israelis set sail from the mouth of the Red Sea and were wrecked of the Kenery Island, fifteen miles from the Cheul creek.’ (History and Culture of the Bene Israel in India, by Principal Moses Ezekiel)

I was now even more curious to know my roots. At that point it was just curiosity. Now, as I grow older, I explore as much as I can about Judaism. My husband told me what his uncle had narrated to him. He said that there had been a shipwreck off the Konkan coast of India, about two thousand years ago. I read that the ship, with the Jews fleeing persecution or for trading purposes, had apparently come from Palestine, through Egypt, via the Red Sea. The ship had struck some rocks and there were seven couples, washed ashore, who were presumed to be dead, by the villagers. When they built a funeral pyre and placed the bodies on it, suddenly, someone observed signs of life in the bodies on the pyre. The villagers took them off the pyre and resuscitated them. Another legend is that today’s Chitpavan Brahmins (Chitpavan, which means, recovered from the funeral pyre- https://www.encyclopedia.com/humanities/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/chitpavan-brahman), were probably the original shipwrecked Jews. They were fair skinned with light eyes, high cheek bones and they had wavy hair.

The survivors then settled in the coastal villages of Naogaon, and other neighboring villages, like Alibaug (where I spent some of the most wonderful days of my childhood with my uncle’s family) and became oil pressers. My uncle owned a grain mill there. The newly arrived folk were known as Shanwar Telis, that is Saturday oil men, since they did not work on Saturdays. Saturday was observed as the Sabbath. The Marathi word for Saturday is Shanivar. (In some accounts you will find that the word, Shanwar, is spelled Shanivar.) The villagers were kind to the newly arrived people, and they in turn blended seamlessly into the life of the Hindus, while still retaining many of their customs and traditions. These include praying The Shema, eating Kosher food, and observing the Sabbath. Of course, since all the sacred texts, The Torah and The Talmud were lost after the shipwreck, naturally the legends were passed on orally.

https://www.livehistoryindia.com/cover-story/2017/07/20/bene-israel—legends-of-the-children-of-israel (this site talks more about the foods they ate, their dress and the Marathi language they adopted).

My father, the late poet Nissim Ezekiel, records the Jewish oil pressers in his poem, which is the first profession they took up, when they arrived in the villages. It is suggested that oil pressing was a trade they knew in Israel, so they were familiar with it.

…My ancestors, among the castes,

Were aliens crushing seed for bread

(the hooded bullock made his rounds)

Nissim Ezekiel ‘Background Casually’

And some lines from my poem ‘Alibaug’, a settlement of the Bene Israeli Jewish people along the Konkan coast.

I miss Alibaug

The hushed whispers between cousins

I don’t know when I can return

To the land of my ancestors

The land of the Shanwar telis, the Oil Pressers,

And from my poem ‘Shipwreck’:

…Settling in nearby villages

Blending into the landscape

They pressed the oil

They became oil pressers

Of the local seed

Saturday oil pressers

Shanwar Telis.

My ancestors

Built homes, married, had children

Multiplied like the grains of sand

As promised to Abraham

I am from the same seed

Descendant of those shipwrecked wanderers…

God’s Rock recurs in dreams

‘My ship’ breaks ever so often

On life’s rocks

But I survive

Like my ancestors,

Pressing seeds into verse

Not just on Saturday,

To preserve a story of survival.

Whenever I read accounts of this legend, the Chitpavan Brahmin part does not come up. Here again, is a discovery made by my husband. He had a close friend in his class in college who was fair, had high cheek bones and light eyes. He asked her if she was Jewish, to which she replied that she was a Chitpavan Brahmin. The pieces of the legend seemed to be falling into place! My poem Shipwreck also talks of the bodies stirring on the funeral pyre.

The Elijah Rock in Alibag from www.elijah-rock.com

Yet another legend, the Bene Israel Jews believe in, is that the prophet Elijah ascended to heaven from the rock in his chariot from where the shipwreck took place. Some claim that this event took place in Haifa in Israel, while the Bene Israel claim that the marks of Elijah’s chariot wheel were found on the rock where the actual shipwreck had taken place. In some accounts, I read that Elijah had visited India twice. Once, when the early Jews arrived, and the second time happened at a much earlier period and this story is recorded in the book of Kings in The Bible (Kings 2: 1-18). It is believed that the prophet stopped near the village of Alibaug and the chariot wheels and the footprints of the horses are still clearly visible. It has become a pilgrimage site for the Jews when they visit from Israel. There are several paintings of this auspicious event.

(Read more at https://www.livehistoryindia.com/cover-story/2017/07/20/bene-israel—legends-of-the-children-of-israel)

My poem ‘Man in White’, is about a figure I repeatedly saw at night, when I lived at my grandmother’s house. I wrote the poem many decades later and concluded that the figure that appeared to me might have been the prophet Elijah. However, I did not specifically name the prophet.

Who was he

This Man in White?

A saint, a prophet, a long-lost soul

Come to protect me from myself

The world’s evil

To bring blessings or to curse?

As I was writing this piece, The Times of India dated February 21st, 2021, had an interesting article featured about the Jewish celebration of the festival of Purim, by the Bene Israeli Jews in Mumbai. It is one of the most joyous festivals in the Jewish calendar. At this time, it is customary to read the book of Esther known as the Megilla. Pictures of this scroll can be found from various sources. The festival of Purim commemorates the salvation of Jews in the Persian empire. It is usually accompanied by a lot of singing and dancing to signify freedom from, and the defeat of, the evil chief minister of King Ahasuerus, Haman, by Queen Esther. (She was reputed to be exceptionally beautiful, as well as a virtuous woman). That is how the legend goes. The connection between the Marathi language, which the Bene Israel community of Indian Jews spoke, and their culture, was re-established through the Marathi-Hebrew kirtans or the songs two octogenarian sisters from Neral (about a two-hour drive from Mumbai, and also accessible by train) were going to sing in a synagogue in South Bombay, if there was not going to be another lockdown. The sisters wanted to celebrate the festival of Purim by their performance in song, aptly titled ‘Esther Ranichi Katha.’ In Marathi, that means the story of Queen Esther.

Magen David Synagogue in Byculla Mumbai, where the parents of the writer were married

I was excited to listen to the kirtans on YouTube and discover one that was familiar. An aunt, living with us at my grandmother’s house had taught it to me. Kirtans are a form of storytelling in song, accompanied by Indian musical instruments. It is an interactive performance, involving the participation of the audience, who sing and clap along with the singers and musicians. The word Kirtan is of Sanskrit origin. The Bene Israeli kirtans are inspired and influenced by the Hindu musical traditions. I have also taken part in Purim celebrations at the synagogue, growing up in Bombay. During this festival, many of the traditional foods were prepared at my grandmother’s house. The link below gives more information about the tradition of Kirtans. The performance in Mumbai was unfortunately cancelled due to COVID-19 restrictions.

https://www.timesofisrael.com/jewish-indian-women-elders-spearhead-revival-of-purim-musical-tradition/?fbclid=IwAR04oteCR7xs3Ii6OLychxMPjYYXwcE8KseBgcQHQw95XLKcMWHyi5HIW7M

I learned several songs in Marathi, also from the same aunt, and am pleased to know that the Bene Israel community are working hard to preserve these songs in notebooks. The article mentions that the song their grandparents sang were about Noah, Moses, King David, and Elijah. The community in Israel are also working hard to preserve the history, customs, and traditions of this important Jewish group. Just one example is the Malida, which is a kind of thanksgiving ceremony (with its accompanying foods and prayers) will now be officially recognized in Israel as the Indian Jewish Bene Israel custom on the festival of Tu Bishvat, which is the Tree planting festival in Israel. The Ministry of Education will now adopt the custom for study in school, a friend from Israel tells me. The Bene Israel Jews group faced much discrimination in Israel, whereas in India they never faced any kind of anti-Semitism at all.

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/mumbai/century-old-marathi-hebrew-kirtans-get-revived-in-the-city/articleshow/81131396.cms

The Bene Israel Jewish community to which I belong, is the largest of the three communities of groups that came to India. The other two groups are the Cochin Jews and the Baghdadi Jews. Here in Canada, where I currently reside, most, in fact, all the people I meet, have never heard of Indian Jews. When I tell them our origins and our ties to India, they express great surprise. In the 50’s and the 60’s there was a mass exodus of Jews from India to Israel. Some of my wonderful aunts and uncles from my mother’s family and an aunt on my father’s side were among those who migrated. Israel is their home, but this generation and their children have strong ties to India. For their grandchildren, born in Israel, this connection is not that important. My aunt would always repeat the phrase ‘next year in the promised land’. She taught herself Hebrew at sixty years of age, to prepare herself for the move. My father chose not to go as he had deep rooted connections to India, and especially to his birthplace, Bombay. In fact, I do not remember any conversations or discussions on the subject. There was never a question of leaving to make a home anywhere abroad. To quote a poem from his section titled Egoist’s Prayers:

Confiscate my passport Lord,

I don’t want to go abroad.

Let me find my song

Where I belong.

The Bene Israel Jews are the most ‘Indianized’ of the three groups of Indian Jews. Whenever I asked my father whether we were Indian Jewish or Jewish Indian, he would reply ‘both.’ The importance of legends cannot be underestimated because they may seem invisible, they add to the fabric of a community’s identity.

♣♣♣END♣♣♣

An Interview with Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca by Susmita Paul

Q. 1. Reminiscences about your childhood are strewn across your recent collection of poetry, such as ‘Light of the Sabbath’. Could you tell us why is it that your childhood surfaces so eloquently in this collection?

Memory is a wonderful thing. It has allowed me to celebrate the warm and loving personalities and places of my childhood in my chapbook, ‘Light of The Sabbath.’ It has allowed me to re-live my childhood days, to walk with my paternal grandmother down the broken sidewalks of Bombay with ‘every square inch teeming with humanity’, to the synagogue to light the lamp, ‘to squeeze the purple grapes of faith’ on sacred Sabbath Fridays, with my aunt, whose faith could move mountains, ‘Those hands that move mountains/ Stirred the curry fluffed the rice/. ’Faith may move mountains’… She is also celebrated in my poem ‘Chain of Events.’ Speaking of the gold chain with a Star of David pendant that she gave me before she left, I wrote in the poem: ‘These are the chains that bind/ Twenty-two carat gold/ into bonds of love’…

It is memory, and not merely nostalgia, that has prompted me to recreate the distinct taste of the China Grass Halwa (Indian pudding) made by another aunt, to eat ‘the curry with ten green chillies when we visited the village of Alibaug, instead of the twenty she usually put in’, referring to my ‘Alibaug aunty’, and to have a ‘jovial uncle with a rich laugh who owned a grain mill and where the grain poured out of the ancient machines like his patient and unselfish love for us’, to name a few of the dear people celebrated in my poems. Despite a challenging childhood due to a complicated family situation, I was blessed with aunts and uncles on both sides of the family, who freely gave me an abundance of unconditional love. The reminiscences of my childhood are celebrations of the relatives that peopled my young world. I would have to put together a whole other book of poems which commemorates my grandfathers, uncles, and my cousins. I do have individual poems about them. My amazing aunt Hannah, whom I celebrate in my title poem, ‘Light of The Sabbath’ more than helped me survive the traumas of some of the loneliest times in my life. She was there at my birth and remained in my life till she made Aliyah to Israel. Her faith and devotion to her God when ‘she read all one hundred and fifty psalms each Saturday’, is something that is indelibly engraved on my mind. My memories capture the essence of these souls, paying tribute to these strong yet gentle extended family members, and immortalizing them in verse.

In the poem about my maternal grandmother, ‘The Ballad of Little Ma’, my memory takes me to my petite, yet strong four-foot eleven inches tall grandmother who ‘spoke less, but when she put her hand on your shoulder/ you knew you were loved.’ And who had ‘no muscles or six pack / just strength of heart and soul.’

My childhood was a magical time, and yet, to borrow that well-known Dickensian phrase from the ‘Tale of Two Cities’, ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.’ My focus in my chapbook was on ‘the best of times.’

Q.2. From the vantage point of your Jewish identity, how important is writing to stop the erasure of socio-religious-political identities?

I was born and raised in the Bene-Israeli Jewish community in Bombay, the largest of the three communities of Jews in India. We were a minority community like the Parsis. Many Jews rose to prominent positions like Dr. E. Moses who was a Mayor of Bombay. Several Jews became prominent doctors, teachers, and lawyers The Jews, like the Parsis, blended seamlessly into the Indian landscape and never faced any discrimination. Many people in the western world express surprise to learn that there are Jews in India. The community of Indian Jews that immigrated to Israel in large numbers in the fifties and sixties by contrast, faced much discrimination in Israel. Indian Jews were not even considered Jewish. Darker skin color and a failure to speak fluent Hebrew are cited as being among the causes of discrimination. Numerous Jews left India for a better life in ‘The Promised Land.’ ‘Next year in Jerusalem’ was the dream of so many Jewish people I met when I was young. To their credit, the Bene-Israelites are making strong efforts to preserve their heritage and even getting some of their traditions like Malida, an Indian Jewish Thanksgiving ceremony, cited in textbooks. They are working hard to assert and retain their identity. Poets, artists, and writers can document this rich heritage through their work and ensure their history and presence is well-established as a significant presence in the world, and not erased. The world has much to gain by learning about diverse minority communities in India, and in other parts of the world as well.

In a New York Times article titled ‘Fighting Erasure’, Parul Sehgal says “Erasure refers to the practice of collective indifference that renders certain people and groups invisible… It goes beyond simplistic discussions of quotas to ask: Whose stories are taught and told? Whose suffering is recognized? Whose dead are mourned?”

We were a liberal Jewish family. At my grandparents’ homes particularly, we observed the customs and traditions of the Indian Jewish community, which are often quite distinct from those of the Western Jews. Since I attended a Christian school and also worked in Christian schools in India and overseas, I learned much about Christianity. As I grew older, I wanted to discover my Jewish roots and see what impact they had on forming my world view and the influence on my life today. In my poem ‘Shipwreck’, I speak about the origins of my people who arrived on the Konkan coast of India as their ship struck a rock, with most perishing, but according to legend, seven couples survived. The fair-skinned, curly-haired light-eyed people arrived over two thousand years ago and settled in the villages there, later moving to Bombay ‘I am from that same seed/ Descendant of those shipwrecked warriors/ God’s rock occurs in dreams/ my ‘ship’ breaks ever so often/ On life’s rocks but I survive/ like my ancestors/ Pressing seeds into verse/ To preserve a story of survival/ Not just on Saturdays.’

In my poem ‘Ancestral Shipwreck’ I also describe the origins of my community.

I arrived on stormy seas/ Flung against a rock by a shipwreck/ I don’t remember who I was fleeing/ Or why I boarded the ship. / The village gave me shelter/ I remembered *The Shema and The Sabbath/ I forgot my language…

Q.3. In writing, we carry the legacy of our ancestors- both biological and literary. How does it affect you, given that your father Nissim Ezekiel is considered the father of Indian poetry in English?

It is a matter of immense pride, along with an equal measure of humility for me, that my father, the late poet Nissim Ezekiel, is widely acknowledged as the Father of Indian Poetry in English. Biologically, I am his daughter, his flesh and blood. My name ‘Kavita’, which means poem in Sanskrit, was perhaps both symbolically and prophetically given to me by my father. Or he might have had a vision, like the prophet Ezekiel! My mother told me that when I was born, my father rejoiced as if he had written his best poem! It is significant that I was not given a Jewish name. In several interviews and presentations about my father I have always maintained that preserving his legacy is near and dear to my heart. It is more important to me than my own writing. Many of the poems I write are either dedicated to my father or make reference to him in one way or another. We shared a deep bond. In my poem ‘Daddy’ I write that ‘the love of words is my steadfast inheritance.’ My father sowed the seeds of my love of words… the beginnings of my literary legacy. My home was always more full of books than any other household object. My father was a voracious reader and poured his love of reading into all three of us. He held informal poetry reading classes in the house, which I attended as a child.

The biological relationship was never one of mere physical connection, his genes to mine. There was a powerful engagement with each other – total acceptance of the other, but also suffering in acknowledging the reality of the other’s life – its strengths, weaknesses, sometimes uncaring, other times, too involved… but never indifference. To me that is the essence of love.

My poem ‘My Father, That Man’ is a poem that speaks of my love and admiration for my father’s passion for words. The last lines express my hope that he has left something of his gift for writing poetry for me. ‘I know that man well/ For he was my father/ I have his flaws/ In my genes/ And perhaps a little/ From his gift of words.’

Q.4. How far do you think Indian poetry in English has evolved since its beginning?

I think every generation of Indian poets writing in English have made a unique contribution to the field of Indian poetry in English. The style and content of pre-colonial poets was very different from poets of the post-colonial generation. It is the same with contemporary poets. In my opinion, it would be somewhat unfair to judge the quality of poetry of various eras by placing them in a sort of direct comparison with each other. Or juxtaposing them to render one seemingly superior and more evolved than the other. I can’t remember the exact source, but when asked if his writing was different from his predecessors, one of the Indian English poets writing in post-Independence (1947) times said, “That’s just the way we wrote.” With contemporary poetry, I find a lot of experimentation with several types of poetry like Haiku, Tanka and Haibun, Prose poetry, to name a few. Also, in keeping with the pressing concerns of the times, the content of today’s poetry reflects themes like Climate Change, Racism, Feminism, and other urgent political and social issues. Several poets have adopted a more colloquial style, which is actually my preference. Translation has also begun to occupy an important space in the field of poetry today.

Q.5. How do you visualize yourself in the poetic arena of contemporary English poetry?

I spend a lot of my time, writing about my father, giving readings of his poetry, lectures, and presentations about him. Preserving his legacy is very near and dear to my heart. I am more than happy to introduce him to the younger generation of poets, that may not be acquainted with him, as well as to international audiences. For me this is a labor of love, and more important than my own writing. Of course, I am a published poet myself and enjoy writing poetry. I have taught poetry in schools and colleges in a teaching career spanning over four decades and published my first book ‘Family Sunday and other poems’ in 1989. Raising two children and working full time consumed the intervening years. I happily, but sometimes wistfully, put my writing on hold. Giving time to my family was important at that stage. It was a priority for me. After a long hiatus, having retired from teaching, I started writing again and my chapbook ‘Light of The Sabbath’ was published in September 2021. My simple desire is to share my most treasured memories and experiences with readers. My greatest reward is when the poems are well-received and have touched the reader is some way. My poems are also a record in verse of my family history. On one occasion, my father, knowing my love of the Beatles, bought me a book of their lyrics from a bookshop in New York. He inscribed the book ‘To Kavita, with faith in her potential.’ If, in some small measure I can fulfil that potential, then I have not only fulfilled his hope for me, but my own dream for myself.

Kavita: Thank you for the opportunity of sharing my thoughts and ideas with you.

Susmita: Thank you Kavita for taking time out of your busy schedule to talk to us. We are filled with gratitude.

Susmita is a creative writer and independent scholar with bipolar mood disorder with schizophrenic potential. She writes in English and Bengali and is published in “Headline Poetry and Press”, “Montauk” and “Learning and Creativity”. Her published books are Poetry in Pieces (2018) and Himabaho Kotha Bole (When Glaciers Speak) (2019). She is the Founding Editor-in-Chief of The Pine Cone Review. Her personal website is www.susmitapaul.org

‘Night of the Scorpion’ and ‘Poet, Lover, Birdwatcher’ | Nissim Ezekiel | Read by Kavita Ezekiel Mendonca

Kavita reading her father’s poems for the University of Hyderabad website (Indian Writing in English)

Interview with Basudhara Roy and Jaydeep Sarangi on the poetry of Nissim Ezekiel